Mental Health in Education in India: Why New Supreme Court Guidelines Matter

In July 2025, the Supreme Court of India in its landmark judgment, Sukdeb Saha v. State of Andhra Pradesh and Others, recognised mental health as being integral to the right to life under Article 21 of the Constitution. For the first time, nationwide, binding guidelines were issued for all educational institutions and coaching centres aimed at addressing the alarming rise in student suicides and the urgent need for effective mental health support in India’s schools and colleges.

The Supreme Court judgment represents a clear shift in judicial approach to student suicide prevention. It moves beyond the Delhi High Court’s earlier reluctance to intervene and goes further than the Supreme Court’s own March 2025 decision which had set up a national task force on ‘Mental Health Concerns of Students and the Prevention of Suicides in Higher Educational Institutions’ to investigate the causes of student suicides, effectiveness of policies, and recommend reforms.

The court’s order requires all educational institutions to adopt a mental health policy, appoint trained counsellors, ban harmful practices like student segregation based on academic performance, conduct sensitisation and counselling activities, revise examination patterns to reduce academic burden and conduct staff training on psychological first aid and recognising early warning signs of distress. These measures will remain in force until the Parliament enacts a dedicated legislation on student mental health. All states/ union territories have two months to notify rules, district-level monitoring committees are to oversee compliance, and the Union government has to file a progress report by 27 October 2025.

Why this matters

India has one of the

While the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 protects the dignity and rights of persons with mental illness2 and guarantees them the right to affordable, quality mental health services, it does not place any obligations on educational institutions, specifically. Efforts such as the proposed 2023 amendment bill and the 2024 Coaching Centre Guidelines sought to address this gap, however the bill has not been passed and the guidelines are not binding in nature. Hence, the Supreme Court’s intervention is significant. It creates a uniform, enforceable framework for mental health support in all educational institutions (public and private) across India. Given the vulnerability of students such guidelines were essential.

Existing Policy Landscape

Although India currently lacks a binding legislative framework governing mental health in educational institutions, the Ministry of Education (MoE) and the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) have introduced several initiatives- ranging from frameworks/ guidelines/ advisories to schemes- to safeguard mental wellbeing. Some of these measures target the general population, while others are tailored specifically for students.

These mental health efforts align with the broader vision of the National Education Policy which seeks to reduce stress by moving away from rote learning and towards assessments that measure conceptual understanding. The introduction of student counselling systems is a key element of this holistic approach.

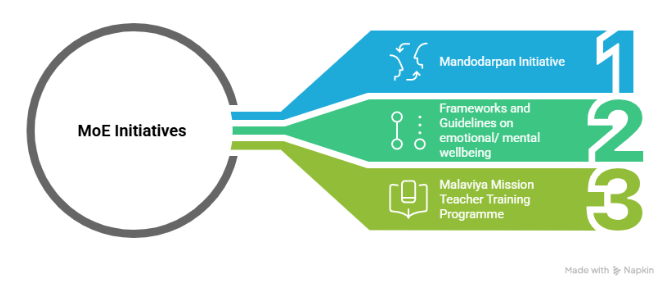

Initiatives by the Ministry of Education

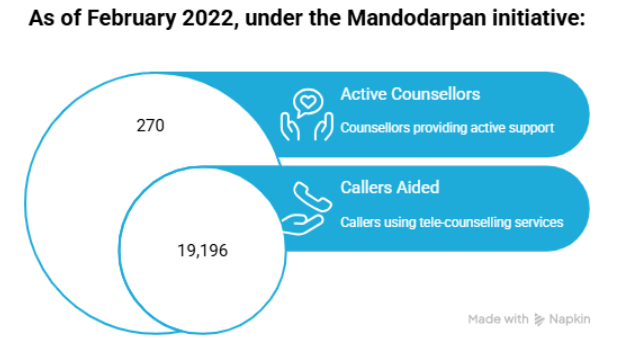

- The Mandodarpan initiative, implemented through the National Council of Education Research and Training (NCERT), provides psychological support to students, and teachers. It includes advisory guidelines, a national helpline offering tele counselling, a database of counsellors and online live interactive sessions. Even HEIs have been advised to participate in this programme.

- Frameworks and guidelines for emotional and mental wellbeing have been circulated to HEIs. These include the Guidelines for ‘Promotion of Physical Fitness, Sports, Students’ health, Welfare, Psychological and Emotional Wellbeing’, ‘Framework Guidelines for Emotional and Mental Wellbeing’, ‘Promotion of Equity in Higher Educational Institutions Regulations’ and National Suicide Prevention Strategy. HEIs have also been directed to share details of MoHFW’s mental health initiatives with students. Further to this, many institutions have established student cells and counselling centres, conducted awareness sessions and introduced mental health screening mechanisms during student induction. These activities are largely funded through the budgetary allocations made to the institutions.

- The Department of Higher Education, MoE, launched the Malaviya Mission Teacher Training Programme, a 100 per cent centrally funded scheme focused on building teacher capacity at HEIs, including training to address student mental health concerns. The scheme, however, has seen slow uptake. In FY 24-25, the initial allocation of ₹100 crores was revised downwards to ₹50 crores at the revised estimate (RE) stage. For FY 25-26, the BE for the scheme is₹70 crore, a 40% increase over the previous year’s REs but 30% lower than the previous years’ BE. It also only amounts to 74% of the department’s projected demand for the year. Between May and October 2024, more than 900 faculty members participated in training sessions under the programme.

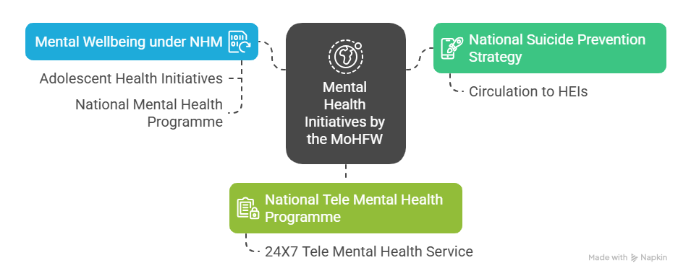

Initiatives by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare

The programmes/ policies implemented by the MoHFW to promote mental wellbeing are as follows:

National Suicide Prevention Strategy: This has been circulated to all HEIs as part of efforts to reduce suicide rates and address mental health concerns.

National Tele Mental Health Programme: Launched in 2022, the NTMHP aims to provide equitable, affordable and quality mental health care through a 24X7 tele mental health service. As of July 2025, 36 states/ UTs have established 53 tele mental health assistance and networking across states (MANAS) cells. More than 23 lakh calls have been handled on the helpline number. A mobile application has also been launched by the government.

However, budget analysis reveals a declining trend in allocations and expenditure:

- From FY 22-23 to FY 24-25, there has been a steady fall in the allocations (from ₹121 crore to ₹45 crore), with allocations in FY 24-25 being 63% lower than that in FY 22-23.

- In FY 25-26 allocations have almost doubled compared to the previous year’s RE, but are still 20% lower than the previous year’s BE.

- Allocations have been significantly reduced at the RE stage every year.

- Fund utilisation remains low- 55% in FY 22-23 and 51% in FY 23-24 due to delays in state-level recruitment and challenges in fund disbursement, as noted by a Standing Committee Report. However, utilisation significantly improved in FY 24-25- as on 12 March 2025 it was 82%.

Mental wellbeing under the National Health Mission (NHM)

Towards Adolescent Health Initiatives: The MoHFW directs part of NHM funding towards adolescent health initiatives, which include adolescent health clinics, iron supplements, menstrual hygiene, Ayushman Bharat School Health and Wellness Programme etc. The latter is implemented in government and government aided schools, training two teachers per school as ‘health and wellness ambassadors’ to conduct interactive sessions on health promotion, including mental health. A review of the allocated budget in the 10 states having the highest student suicide rates3 reveals:

- In FY 24-25, except for Chhattisgarh (0.4%) and Gujarat (0.3%), states allocated a negligible share of their health budgets towards this programme.

- In Jharkhand, Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh and Rajasthan the allocated budget increased between FY 23-24 and FY 24-25 (in Rajasthan it increased by more than 4 times). In other states, the allocated budget declined, with Tamil Nadu recording the steepest drop- 92% lower than the previous year

- Utilisation rates vary sharply between states and years. In FY 23-24, Gujarat (70%) and Uttar Pradesh (55%) had the highest utilisation rates. In FY 24-25 (up to November 2024), Tamil Nadu utilised 100% of its allocated budget, while Jharkhand utilised 95%, a significant rise from the previous year when utilisation was 3% and 26% respectively. Further, utilising spillovers, Uttar Pradesh utilised 115% of its allocated budget in FY 24-25. No funds were utilised, however, in Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh.

The National Mental Health Programme (NMHP): A key component of the NMHP is the District Mental Health Programme (DMHP) which expands human resources in mental health, supports early detection and treatment of mental health conditions and promotes public awareness on mental wellbeing. In addition to the DMHP, states also receive NMHP funds for state-specific initiatives4. Analysis of trends shows that:

- With the exception of Tamil Nadu which allocates 0.8% of NHM funds towards the NMHP, other states allocate less than 0.5%.

- In FY 24-25, allocated budgets for the NMHP declined in 5 states. The sharpest fall was in Jharkhand (29%).

- Tamil Nadu recorded the largest rise in allocated budget in FY 24-25, more than doubling its NMHP allocation in FY 24-25 as compared to the previous year.

- No state achieved full utilisation of NMHP funds in either FY 23-24 or FY 24-25. Andhra Pradesh utilised 82% of its allocated budget in FY 23-24, and 57% in FY 24-25. Maharashtra and Chhattisgarh recorded very low utilisation in FY 24-25 (9%).

Hence, the Supreme Court’s guidelines arrive against a backdrop of fragmented, under-funded mental health initiatives and are a promising step. The court has made mental health in education a legal mandate. If effectively implemented this could transform how India’s educational institutions support student wellbeing.

Endnotes

1 The Mental Healthcare (Amendment) Bill, 2023, Statement of Objects and Reasons

2 Section 2(s) of the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 defines ‘mental illness’ as “a substantial disorder of thinking, mood, perception, orientation or memory that grossly impairs judgment, behaviour, capacity to recognise reality or ability to meet the ordinary demands of life, mental conditions associated with the abuse of alcohol and drugs, but does not include mental retardation which is a condition of arrested or incomplete development of mind of a person, specially characterised by subnormality of intelligence”.

3 As per the 2022 National Crime Records Bureau Report.

4 Only 5 of the 10 analysed states- - Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand and Karnataka- allocate funds towards state specific initiatives in FY 24-25.